Este post também poderia se chamar “o leitor aflito”. Ou apressado, ansioso, insano...

“Not only is my story designed to delight and

entertain, but there is a kernel of truth hidden within, where only the

cleverest student might find it.” His expression turned mysterious. “All the

truth in the world is held in stories, you

know.” (p. 390).

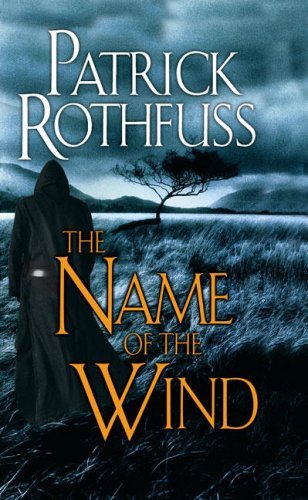

Na semana passada, li o segundo livro da

trilogia de Pat Rothfuss, The Wise Man’s Fear. O Temor do Homem Sábio já está

editado em português pela Arqueiro, num tijolão de quase mil páginas. Mas eu o li

no arquivo para computador, numa jornada meio animal contra a minha própria

ansiedade.

O segundo livro da história de Kvothe,

“uma lenda viva do próprio tempo”, traz o segundo dia das narrativas de sua

história ao Cronista e ao seu discípulo Bast – por quem eu me apaixono cada vez

mais. E não só por ele, vale dizer. Os personagens que já conhecemos crescem e

apresentam outras facetas... novos aparecem ao longo da jornada de Kvothe até

se tornar o perseguido número um do mundo em que vive.

So yes. It had flaws, but what does that matter when

it comes to matters of the heart? We love what we love. Reason does not enter

into it. In many ways, unwise love is the truest love. Anyone can love a thing because.That’s as easy as putting a penny in your pocket. But

to love something despite. To know the

flaws and love them too. That is rare and pure and perfect. (p. 68).

Kvothe é um Contador de Histórias por

direito de sangue. Seu povo, os Edema Ruh, são nômades que percorrem os diferentes

reinos, levando a arte para os povoados, em narrativa, interpretação e música. Assim que

Kvothe vive suas aventuras fantásticas com a língua sempre afiada, a capacidade

de improvisar diante das mais bizarras situações e o alaúde, seu instrumento,

nas costas - quando ele não está penhorado, claro.

Mas, o mais importante: como bom herói,

lenda e contador de histórias, ele traz a morte ao seu encalço e um coração

absolutamente partido.

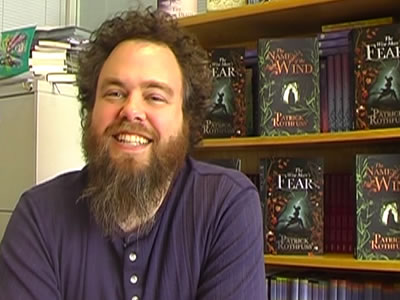

No primeiro livro, Rothfuss, um Edema

Ruh himself, deixou tantas, mas tantas perguntas no ar, que entrei no segundo

livro com a esperança de algumas respostas. Afinal, para que ele apresentaria

mil páginas se não para nos dar respostas.

O que é a ilusão do ego profano e da

mente perturbada.

Algumas pistas, muitas novas perguntas e

várias teses a respeito do que virá no terceiro dia das narrativas de Kvothe ao

cronista mais sortudo do universo, isso foi o que encontrei. Como Kvothe,

comecei numa aflição apressada de ter minhas respostas. Lá pela página 500, eu

maldizia terrivelmente a raça de Rothfuss e soltava nomes não muito elogiosos, diante da tela do computador,

sobre esse segundo livro. WTF? Eu pensava. Nada vai acontecer??? Pela página

700, junto com Kvothe em sua jornada espiritual pelo Ademre, comecei a entender

melhor o que tinha diante dos olhos. E,

na última página do livro, 1024 no ebook, eu me maravilhava com a capacidade de

criar um herói, seu mundo e sua jornada de Patrick Rothfuss, esse insano Ruh.

We live in a civilized age, and few places are more

civilized than the University and its immediate environs. But parts of the iron

law are left over from darker times. It had been a hundred years since anyone

had been burned for Consortation or Unnatural Arts, but the laws were still

there. The ink was faded, but the words

were clear. (p.

369). .

Muitas questões ficam para o terceiro

dia, que só chegará ano que vem. Nesse tempo que falta – e que me pareceu

insuportavelmente longo quando fechei o livro –, com certeza andarei pelos dois

livros novamente. Estou apenas esperando o coração acalmar, rs.

That thread of truth

wove through the story, gave it strength. (p.701).

Outra alternativa, além da busca

incessante por novas e maravilhosas histórias, é dar uma passada de vez em

quando pelo site oficial de Rothfuss e seu blog. Ver as opiniões dessa figura

insana enquanto dá um destino a Kvothe e à confusão que ele apronta é um

consolo pela espera infinita – como ela parece no momento!

Sei que muitas das citações não fazem

sentido fora do seu contexto... Mas algumas contam de coisas que ultrapassam o

mundo de Kvothe e atingem o meu. Assim, eu as coloco aqui.

Adoro a delicadeza

das imagens nas conversas de Kvothe com Auri, de quem ainda não sabemos muito,

só que seu mundo se quebrou de alguma forma:

“What did you bring me?” I countered.

She grinned. “I have an apple that thinks it is a

pear,” she said, holding it up. “And a bun that thinks it is a cat. And a

lettuce that thinks it is a lettuce.”

“It’s a clever lettuce then.”

“Hardly,” she said with a delicate snort. “Why would

anything clever think it was a lettuce?”

“Even if it is a lettuce?” I asked.

“Especially then,” she said. “Bad enough to be a

lettuce. How awful to think you are a lettuce too.” She shook her head sadly,

her hair following the motion as if she were underwater. (p. 47).

Nas narrativas do segundo dia, encontrei

leitores tão aflitos e apressados quanto eu – Simmon e Willen, mos melhores

amigos de Kvothe, esperam por um sentido claro e incontroverso na história do menino que tinha uma fechadura de ouro no umbigo. Estão na

história errada, rs:

“IS THAT THE END?” Simmon asked after a polite pause. He was on his back,

looking up at the stars.

“Yes.”

“It didn’t end the way I thought it would,” he said.

“What did you expect?”

“I was waiting to find out who the beggar really was.

I thought as soon as someone was nice to him, he would turn out to be Taborlin

the Great. Then he would give them his walking stick and a sack of money and .

. .I don’t know. Make something magical happen.”

Wilem spoke up. “He’d say, ‘Whenever you are in danger

knock this stick on the ground and say “stick be quick,” ’ and then the stick

would whirl around and defend them from whoever was attacking them.” Wilem was

lying on his back in the tall grass, too. “I didn’t think he was really an old

beggar.”

“Old beggars in stories are never really old beggars,”

Simmon said with hint of accusation in his voice. “They’re always a witch or a

prince or an angel or something.”

“In real life old beggars are almost always old

beggars,” I pointed out. “But I know what kind of story you two are thinking

about. Those are stories we tell other people to entertain them. This story is

different. It’s one we tell each other.”

“Why tell a story if it’s not entertaining?”

“To help us remember. To teach us—” I made a vague

gesture. “Things.”

“Like exaggerated stereotypes?” Simmon asked.

“What do you mean by that?” I asked, nettled.

“ ‘Tie him to the wagon and make him pull’?” Simmon

made a disgusted noise. “I’d be offended if I didn’t know you.” (p. 324).

Kvothe e o Cronista, uma história que promete muito

ainda:

“It’s a gift,” Kvothe said.

“You think I want this?” Chronicler said

incredulously. “Fame?”

“Not fame,” Kvothe said grimly. “Perspective. You go

rummaging around in other people’s lives. You hear rumors and go digging for

the painful truth beneath the lovely lies. You believe you have a right to

these things. But you don’t.” He looked hard at the scribe. “When someone tells

you a piece of their life, they’re giving you a gift, not granting you your

due.”

Kvothe wiped his hands on the clean linen cloth. “I’m

giving you my story with all the grubby truths intact. All my mistakes and

idiocies laid out naked in the light. If I decide to pass over some small piece

because it bores me, I’m well within my rights. I won’t be goaded into changing

my mind by some farmer’s tale. I’m not an idiot.”

Chronicler looked down at his soup. “It was a little

heavy-handed, wasn’t it?”

“It was,” Kvothe said.

Chronicler looked up with a sigh and gave a small,

embarrassed smile. “Well. You can’t blame me for trying.”

“I can, actually,” Kvothe said. “But I believe I’ve

made my point. And for what it’s worth, I’m sorry for any trouble that might cause

you.” He gestured to the door and the departed farmers. “I might have

overreacted a bit. I’ve never responded well to manipulation.”

Kvothe stepped out from behind the bar, heading to the

table near the hearth. “Come on now, both of you. The trial itself was tedious

business. But it had important repercussions.” (Pp. 390/381).

Algumas verdades universais:

Teccam explains that there are two types of secrets.

There are secrets of the mouth and secrets of the heart. Most secrets are

secrets of the mouth. Gossip shared and small scandals whispered. These secrets

long to be let loose upon the world. A secret of the mouth is like a stone in

your boot. At first you’re barely aware of it. Then it grows irritating, then

intolerable. Secrets of the mouth grow larger the longer you keep them,

swelling until they press against your lips. They fight to be let free.

Secrets of the heart are different. They are private

and painful, and we want nothing more than to hide them from the world. They do

not swell and press against the mouth. They live in the heart, and the longer

they are kept, the heavier they become.

Teccam claims it is better to have a mouthful of

poison than a secret of the heart. Any fool will spit out poison, he says, but

we hoard these painful treasures. We swallow hard against them every day,

forcing them deep inside us. There they sit, growing heavier, festering. Given

enough time, they cannot help but crush the heart that holds them. (p. 532).

You must also come to understand the fine shades of meaning.

(p.

797).

Saí de uma história incrivelmente bem contada para uma outra totalmente ugh.

Com os livros de Richelle Mead eu me

divirto muito, muito. E o meu coração se abala seriamente com alguns dos

reverses nas histórias. Foi assim ao final do terceiro livro de Vampire Academy, um ponto de separação

entre a história mais leve até então e a pancadaria heartbreaking que rolou a

partir do quarto livro. Tudo bem que ela quase pôs tudo a perder no último e

sexto livro... Nos livros de Georgina

Kinckaid, uma sucubus que vive em Seatle, tem um chefe demônio com o rosto

de John Cusack (muito bom isso) e tem um

amor impossível com Seth, o escritor fofo, a história ficou mais triste também

a partir do terceiro livro. Bloodlines,

um spin-off de Vampire Academy e,

para mim, a razão da série de Rose e Dimitri ter ficado sem um fim decente,

está no segundo livro ainda e, portanto, bastante leve.

Com os livros de Richelle Mead eu me

divirto muito, muito. E o meu coração se abala seriamente com alguns dos

reverses nas histórias. Foi assim ao final do terceiro livro de Vampire Academy, um ponto de separação

entre a história mais leve até então e a pancadaria heartbreaking que rolou a

partir do quarto livro. Tudo bem que ela quase pôs tudo a perder no último e

sexto livro... Nos livros de Georgina

Kinckaid, uma sucubus que vive em Seatle, tem um chefe demônio com o rosto

de John Cusack (muito bom isso) e tem um

amor impossível com Seth, o escritor fofo, a história ficou mais triste também

a partir do terceiro livro. Bloodlines,

um spin-off de Vampire Academy e,

para mim, a razão da série de Rose e Dimitri ter ficado sem um fim decente,

está no segundo livro ainda e, portanto, bastante leve. Com outra série de Mead, Dark Swan, eu tive um certo receio desde

o início. Comprei os dois primeiros livros (são quatro) e os li de relance,

achando todos os dois muito ruins. Mas, com o coração meio em frangalhos ao

final do Segundo Dia de Kvothe, resolvi chegar à serie de forma mais série e dar

mais uma chance à história de Eugenie, shaman caçadora de demônios, para quem

ela é conhecida como Odile, o Cisne Negro.

Com outra série de Mead, Dark Swan, eu tive um certo receio desde

o início. Comprei os dois primeiros livros (são quatro) e os li de relance,

achando todos os dois muito ruins. Mas, com o coração meio em frangalhos ao

final do Segundo Dia de Kvothe, resolvi chegar à serie de forma mais série e dar

mais uma chance à história de Eugenie, shaman caçadora de demônios, para quem

ela é conhecida como Odile, o Cisne Negro.

Ao ler os comentários dos leitores no

amazona.com, tive mais certeza ainda, se é que precisava de uma confirmação.

Essa série é pavorosa mesmo e dela, infelizmente, já desisti.

Para dizer um pouco de como é difícil

largar uma história assim, trago Rothfuss novamente:

He can’t feel a thing

halfway.

The Wise Man’s Fear, p. 953.

PS: Ao chegar o site oficial de Patrick Rothfuss, encontrei, em seu blog, um post sobre algumas memes de Kvothe que ele encontrou na internet. Ele diz que teve sentimentos bastante ambivalentes a respeito... isso, talvez, para ser mais diplomático. São muitas, só no link que ele postou. Nas primeiras eu ri, mas aos poucos fui me irritando. Fora do contexto, tudo ficou muito bobo, mesmo que algumas frases sejam certeiras. But, como comentei no blog, fatos não contam uma história, né?